Below is an interview Paul conducted with Clive Barker for FantasyCon Booklet 2006.

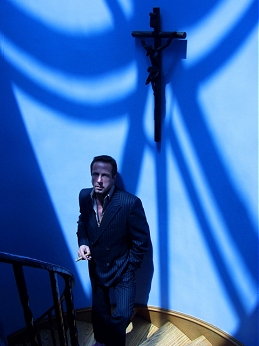

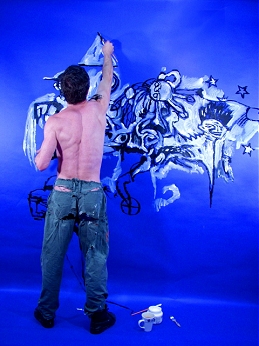

All photography on this page (C) David Armstrong

Clive Barker: Hello Paul.

Paul Kane: Hello Clive, how are you?

Clive Barker: I’m well man, how’s it going?

Paul Kane: Fantastic. Thanks for talking to us.

Clive Barker: My pleasure.

Paul Kane: Well, first question is how do you feel about the British Fantasy Society? And your association with the BFS?

Paul Kane: It is. Do you have any memories from those days, of FantasyCons or anything like that?

Clive Barker: I tended to take a slightly low profile at the FantasyCons, at least that’s my memory of how I performed; other people might think differently. But I’ve always been a lot more shy than my reputation suggests; I put on a bit of a public face, a kind of ‘hail fellow, well met’ kind of thing. But I’m actually wretchedly shy, which I’ve only recently comes to terms with and sort of owned up to; I was really introspective. And I think in many ways the art forms that I’ve chosen to practice, most strongly painting and writing, are attractive to me in no small part because they are solitary, you know?

Paul Kane: Yeah… But as a creative person did you set out consciously to explore every kind of medium or was that something that just happened along the way?

Clive Barker: No, I think you certainly look at things and say, well, could I have a crack at that? And you ask yourself, could I be an ice dancer? No. Could I have written Phantom of the Opera? Thank God, no. But there are things along the way; I’ve obviously looked at illustrated stories a lot, whether they come in the form of Blake’s mythical writings which are so gloriously combined with pictures, I don’t think illustrated is the right term because he produced such beautiful pictures – the images and the words have equal value, which I hope is true of the Abarat books as well.

Paul Kane: Yeah, yeah.

Clive Barker: Which is obviously the fruit of that kind of study.

Paul Kane: Absolutely, yeah.

Clive Barker: So I look at something along the way. I’ve looked at some poetry once in a while, thought I’d have a crack at writing some of that. I’ve done that a little bit, and will hopefully write some more. I’d certainly like to write a play or two more before I shuffle off this mortal coil. And I’d like to write another movie or two, it’s just a question of finding time.

Paul Kane: So is that a factor in whether you’re going to direct again, or do some more work in the theatre?

Clive Barker: It’s time, Paul, yeah. I mean I’m on the final draft of Scarlet Gospels…

Paul Kane: Fantastic.

Clive Barker: I’m on page 1,959.

Paul Kane: Of how many, Clive?

Clive Barker: How many drafts?

Paul Kane: How many pages?

Clive Barker: Ah, well it’ll finish when it finishes (laughs).

Paul Kane: Ahh (laughs)

Clive Barker: These are big buggers, you know. There’s no way of doing them…I mean, I hear people saying it’d go so much faster if you type it in, but I’m an old fashioned kind of guy. What works for me works for me, and I tend to be loyal to the things which work best for me.

Paul Kane: I once saw something where you said that the creative marks on the page also helped?

Clive Barker: I do little doodles sometimes in the margins, how a creature might look or how a street might be arranged or how a world might be arranged, which I need to go back to and reference later on. Or I’ll play through particularly inventive variations of invented names. I really try and do that. I do like the fact that on this page that I’ve almost finished there are one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve…thirteen smaller scribblings and one entire line scribbled out. And the nicest thing about that is I can still see what’s beneath it, which is useful because when I come to do the final polish it will have been typed out, and I’ll have this by my side – I’ll tend to go back to the handwritten draft and peer through the scribbling. And sometimes I’ll find that the first decision, the first choice I made was the better of the two.

Paul Kane: How do you keep track of everything, all the different names and the places?

Clive Barker: I tend to be very good with that. The only part of my mind that’s organised is the part related to the fiction. Everything else is f***ing chaos.

Paul Kane: It’s not a bad thing.

Clive Barker: Yeah, I’ve got my priorities right at least, Paul. But I know where the book is. At any given time I know where the book is. I know what problems there are, where I’ve got to go next and how I’ve got to get there. And if I don’t know how I’m going to get there I know that my problem between now and tomorrow morning when I put the book down tonight, which will be perhaps six o’clock at night to go painting, and by 8:39 the following morning when I pick it up again I need to have solved a problem related to geography, or a problem related to motivation before I pick up the pen again. You can’t dither, it’s a quarter of a million words – you can’t be insecure. You just have to trust in your own madness…I like that phrase actually. I’ve never thought of that before, you’ve dragged that out of me (laughs)

Paul Kane: It’s quotable (both laugh)

Clive Barker: It is, it’s quite quotable. Barker trusts in his own madness. It’s so horribly true, Paul, that’s the thing (both laugh). It’s all true…

Paul Kane: You’ve called it - the creative process - dreaming with your eyes open, but have you ever included anything from an actual dream you’ve had?

Clive Barker: Oh God yes. Lots.

Paul Kane: Any examples?

Clive Barker: Pinhead.

Paul Kane: He came from a dream?

Clive Barker: Yeah, yeah. This is off the…well, this needn’t be off the record, actually. You reach me half an hour after an incredible sort of coincidence that’s happened. Harry D’Amour in The Scarlet Gospels - the hero of The Scarlet Gospels - is pursuing Pinhead across the landscape of Hell; I won’t tell you what Pinhead’s plot is, but he does have one.

Paul Kane: Excellent.

Clive Barker: Halfway across Harry is given access to a vision of Christ which he doesn’t necessarily particularly want, but he gets it anyway. I won’t tell you the circumstances, because that’s sort of fun – the way it comes about.

Paul Kane: It’s whetting my appetite.

Clive Barker: Christ’s on a cross and Harry’s drawn in this vision very, very close to Christ. And he can see the barbs of the thorns, how deeply they dig into the flesh of Christ’s head. And what he hadn’t realised was that Christ feels the same way as Pinhead does. I’d never thought of that, in all the years I’d been thinking about Pinhead, it never occurred to me that Pinhead is wearing an organised crown of thorns. But he is essentially, right?

Paul Kane: Yeah, of course.

Clive Barker: (Quoting) ‘Harry says, “There’s another who’s been at the back of my head and I couldn’t think who it was. But I’ve remembered now.” Christ says, “What about the other?” “His head is pierced like yours, not with thorns but with nails.” Christ says, “How he must suffer.” “You think so?” “Oh, I’m certain. So have him come to me, I would turn him, I would bring him into the circle of my suffering.” Harry says, “He has done terrible things.”’ And then the conversation gets a lot darker (both laugh). It suddenly gave this wonderful chance to have Christ say, “Well bring him on over! It’ll be fine. We’ll chat – he’s had some nails, I’ve had some thorns…”

Paul Kane: Similar…

Clive Barker: But it’s funny I should live with a piece of mythology, a piece of imagery as long as I’ve lived with Pinhead, and got to twenty years of living with him, as it were, and had never made that connection before.

Paul Kane: Well, of course, there’s a scene in Hellraiser III, where Pinhead is in the church…

Clive Barker: Even there I don’t think Hickox is pointing us necessarily to the suffering, or the particular suffering of being pierced in the head.

Paul Kane: No, no.

Clive Barker: I don’t remember blood running from the nails, for instance…Do they?

Paul Kane: That’s right; no I don’t think they do.

Clive Barker: I’m not saying this is a revelation, I’m sure lots of people have thought of this before me. It’s just a case of the author being incredibly frigging slow (laughs).

Paul Kane: Hardly… So what was it like returning to horror territory?

Clive Barker: It’s fun and it’s hard at the same time. It’s fun because there’s a lot of shit out there, but it also does have a grandeur of storytelling which I haven’t been able to apply to horror, until…well, since going back to Damnation Game. I think in some ways this is the book that…I think the two books this novel will remind people of are Imajica and Damnation Game.

Paul Kane: Excellent.

Clive Barker:Damnation Game obviously for the horror, and Imajica for the landscape. Because once you get into Hell, which is the final third of the novel, it’s no Hell you’ve ever seen before – and that’s always fun.

Paul Kane: How does it feel to have created so many of these mythos which are going to live on for years to come?

Clive Barker: Well, I think it’s a lovely thing when something you make moves people enough that they want to do something with it for themselves. And I’ve never understood people bitching about, “Oh you must be pissed off about what he did with this, or what she did with that.” No. I mean to me, once you put the thing out there, it becomes part of the texture. There was a wonderful piece of academic writing done a few years ago about the influence of the Candyman mythos on the people of Cabrini-Green in Chicago, except that the academic in this case did not know that the story had been entirely invented. And she wrote the whole thing as though there really was an original myth. And I though that was perfect; that was the whole thing coming full circle. That was the myth becoming reality for a bunch of people. And when Tony Todd goes – and I actually witnessed this, it doesn’t need to be in Cabrini Green; I’ve seen it in Toronto, with a bunch of black kids going, “Candyman, Candyman!” They do it. Tony just gives them a dark look, you know. It’s great. What I like about it is I used to have a dentist’s assistant and she was this wonderful woman, she had lots of kids. And she said, “You know how I get them to go to sleep at night?” I said, “No.” She said, “I go to the mirror and say, ‘Candyman, Candyman…’ And by number three they’ve all gone…”

Paul Kane: There’s no greater legacy than that.

Clive Barker: Oh no - that’s tip top, isn’t it.

Paul Kane: It is. Just one final question, which gives you the most pleasure: writing or painting?

Clive Barker: When I’m painting, it’s writing…(both laugh) You can finish that yourself…

Paul Kane: I can. Absolutely. Well, I’d better let you get back to it…

Clive Barker: Yes, I’d better get back to Christ.

Paul Kane: Thanks for talking to us, Clive.

Clive Barker: My pleasure, Paul.

Interview (C) Paul Kane & Clive Barker, September 2006.

Photography (C) David Armstrong