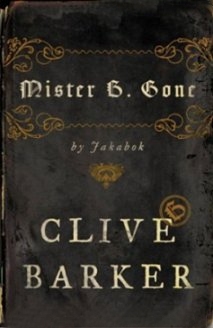

HarperCollins. Hardback, UK: £15, US $24.95

I was so excited sitting down to read this book, which marks Clive Barker’s official return to the horror genre. Some, myself amongst them, would argue he never really left it, nor should genre boundaries matter, but that’s an argument for another time. The fact remains that the subject of this short novel is a demon. But if you’re expecting the kind of demon Barker has dealt with in the past, however, such as the graceful, eloquent yet sadistic Pinhead or the mischievous Yattering, think again. Jakabok Botch is an altogether different kind of creature.

The novel is written from the first person point of view of Jakabok, who is inside the book and relentlessly pleads with the reader to burn it because of the danger the words present. As with many of Barker’s texts, the forbidden nature of those words only makes them more tantalising and as we read on we are granted flashbacks of Jakabok’s life – starting with his turbulent upbringing as one of the Demonation (he and his family live in the ninth circle of Hell). Scarred by fire, he flees from a violent father and hateful mother, and he winds up in our world during the middle ages; a pivotal time for mankind where religious zealots makes the rules. There he befriends Quitoon and the pair go travelling together. But when it becomes apparent that something is happening in the town of Mainz that will change the course of human history, they decide to investigate. And what Jakabok discovers about Heaven and Hell will change his life beyond all recognition as well.

The very clever thing that Barker does with this book is to blend the real with the unreal, something he has become very good at over the years. The descriptions of Jakabok’s early life could be about any average teen on Earth who feels like an outsider. His relationship with Quitoon is a fascinating observation of friendship and unrequited love, with all the ups and downs that entails. And the demonic exploits are purposefully played down so as to not distract you from the true messages of the novel – after all, such scenes of bloodletting would be commonplace to the demon describing it. Similarly, Barker uses the shorthand of Dante’s Inferno which everyone knows, to immediately place us in a Hell we’re ‘comfortable’ with, rather than spending pages describing a new one.

As in Cabal and The Hellbound Heart, the human characters are often the true monsters, more brutal than anything in Hell (for instance, one set of characters take pride in catching and boiling demons for pleasure). And the main protagonist feels completely real to the reader, so much so that he sparks conflicting emotions of love and hate. Make no bones about it, his is a tragic story – but it is also an important one, because his life intersects with an amazing discovery. Barker’s writing draws you in from page one and doesn’t let you go (it’s how he describes the writing process as well, with Jakabok calling to him every day). If this was his breather before engaging in the epic work of the Scarlet Gospels, then we can definitely expect huge things from that tome.

As a statement on the human condition, on life, love and the power of the word over image, and just as a damn fine read, I can’t recommend this highly enough.

(C) P. Kane 2007